In a rare departure, we are pleased to feature breaking news in the world of train songs today. In Carrboro, the state of North Carolina is unveiling a marker to honor Elizabeth Cotten, a resident famous for her song “Freight Train.” The linked article from the Raleigh News-Observer relates the whole tale, but as the story goes, as a teenager Cotton would sit outside her house and watch trains fly by on the Norfolk Southern Line. Inspired by this sight, she penned Freight Train, a simple ode to the Iron Horse. A bit of a morbid song coming from a teenager, “Freight Train” marvels at the speed of the train, and Cotten asks to be buried near the tracks when she dies so she “can hear old number 9 as she comes rolling by.” After marrying and moving out of the area, she mostly gave up guitar for decades, before she was discovered by the Seeger family in the 60s.

This is our first entry in the category of train songs and historical markers, but its an interesting question to consider which train songs are linked to a physical site like this. This is not the first historical marker linked to a train song – the wreck of the Old 97 in Danville, VA has a marker as well. Beyond this wreck, all train wreck ballads are associated with some particular location, though many of these are not well preserved. For understandable reasons, railroad corporations are not particularly eager to mark out tragedies like these, and many of the sites of these wrecks occurred remain active rail lines, out of the reach of tourists’ prying eyes.

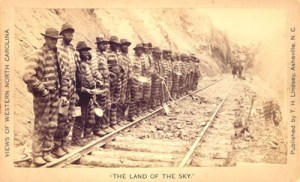

Swannanoa Tunnel in North Carolina, immortalized in song by Bascom Lamar Lunsford, among others, and site of a tragic cave-in, has a marker as well.

There are surely more of these out there, and this is a topic we will have to return to, but for now its nice to have a train-song related historical marker for something positive. The landscape of Carrboro, like many old railroad towns, remains dominated by the railroad, so the marker surely will integrate well into the area. Tracks run directly through the town, and one can grab dinner at the Southern Rail restaurant, or down a stiff drink at the Station, an old depot renovated and turned into a bar. If nothing else, this story gives us an excuse to head back to Carrboro sometime to check out the marker and the area’s great string of watering holes. Kudos to my new state of North Carolina for putting up the sign!